Sophia in ’t Veld is a Member of the European Parliament from The Netherlands and the fourth most politically influential MEP in the area of Democracy and Home affairs. Her party, Democrats 66, is part of the Renew Europe Group, the successor to the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) group Renew Europe describes itself as centrist and considers as its central issues sustainability, rule of law and economic growth. Other prominent European parties of the same group include French President Emmanuel Macron’s La République en Marche and Irish Fianna Fàil; the Bulgarian ethnic party Movement for Rights and Freedoms is also part of the same family.

Sophia in ’t Veld has been chairing the Rule of Law monitoring group in the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) since 2018, and has worked on establishing an EU mechanism for the rule of law. During a recent hearing in LIBE, Mrs. In ’t Veld questioned the Vice-president of the European Commission Vera Joùrova on Bulgaria media freedom and lack of accountability of the Prosecutor General. This prompted us to sit for an interview with her, during which we discussed in what way addressing ongoing protests in Bulgaria reveals key deficiencies in the way Europe functions politically, what can we expect from the new Report on the Rule of Law, and does Brussels actually know what is going on in the poorest and most corrupt member of the EU.

You have been an MEP since 2004. Hungary and Poland joined the EU that same year, Bulgaria followed in 2007. Can you recall what were the expectations back then towards the former Eastern Bloc countries?

We probably thought that economic reforms and preparing them for the internal market would automatically turn them into model democracies. I think those expectations were never realistic.

On the other hand, I also feel that currently there is a tendency to divide Europe into the enlightened, democratic West, and the Eastern countries which are prone to corruption and authoritarianism. That is not accurate. Authoritarianism is on the rise everywhere, look across the pond: Trump is behaving like many of the authoritarian leaders in Eastern Europe, and we also have political parties with the same corrupt authoritarian program as many Eastern countries, they just happen to not have the majority. So this East-West contrast is a false one.

How can we address this rise of authoritarianism at a European level in that case?

You cannot make policies if you do not have shared values; it is a mistake to think that the EU is just an internal market and that values do not count. Just think of governance of the Internet, privacy, AI, freedom of speech, disinformation, police and justice cooperation – all these require a common set of values, rules and standards. We see with Poland, for example, that this is going horribly wrong, judges in the Netherlands and other countries are now refusing to extradite suspects to Poland because they do not trust the judiciary anymore.

If you do not have a properly functioning judiciary, free media, and transparency rules, then you cannot fight corruption; if you have corruption – the internal market cannot function properly. So it is all connected.

The question of values naturally leads us to Bulgaria. You are a member of the LIBE Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs which recently criticized Vice President Vera Jourova on the situation in Bulgaria, where people have been protesting for over two months now. How did Bulgaria become a topic of discussion?

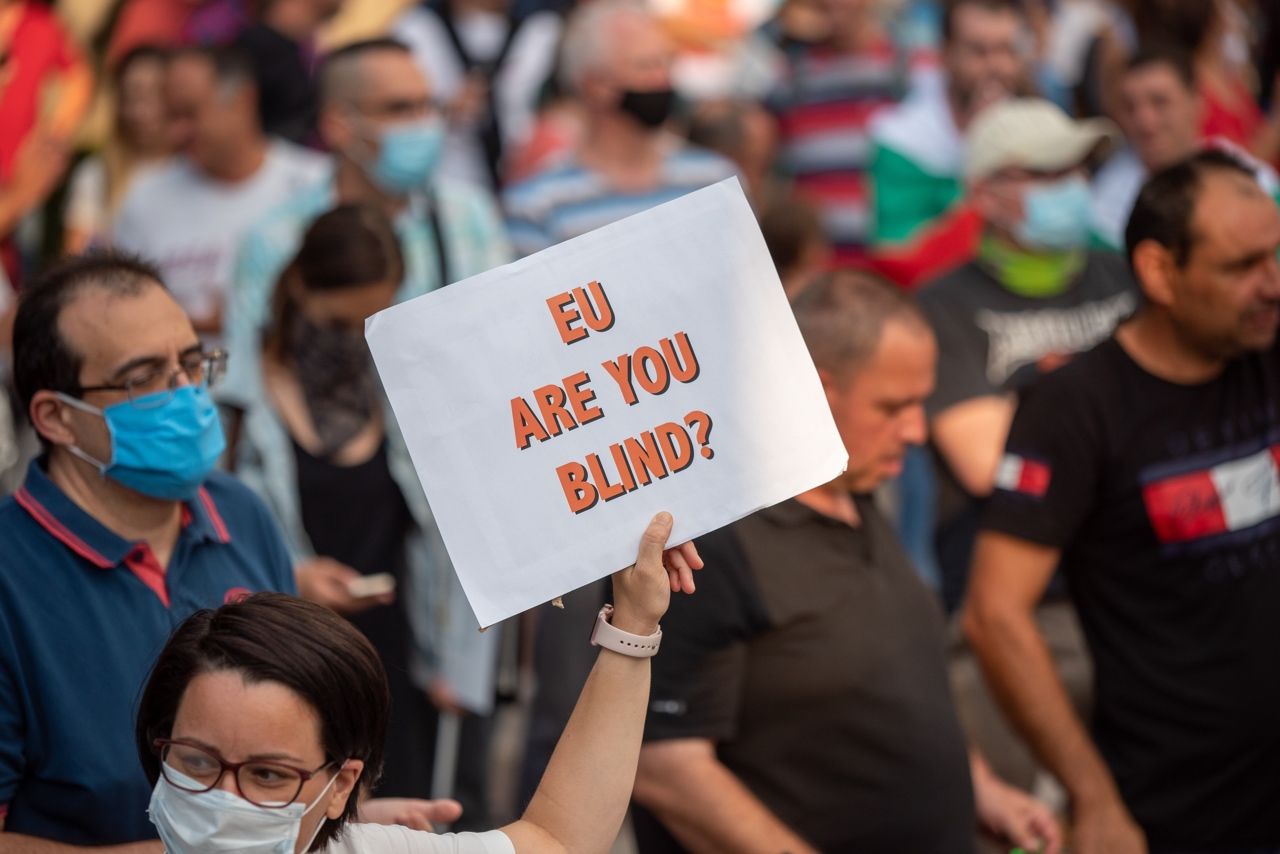

Bulgaria and Romania have always been on the radar screen because there are concerns of corruption, so that is nothing new. We have seen in recent months the massive street protests and the response by the authorities, which triggered concern. We have also seen a number of other concerns. There is the famous court ruling from 2009 saying that the independence and accountability of the General Prosecutor has to be revised. We hear there are concerns over the treatment of Roma people, hate speech, Bulgaria also refuses to ratify the Istanbul Convention.

Hungary and Poland have been in the spotlight for some time now, Malta and Slovakia for a couple of years, now Bulgaria. Later this month the Commission is going to issue – for the first time ever – a Report on the Rule of Law, which will be a cyclical annual event and the follow-up to the legislative initiative taken by the European parliament; I had the pleasure to be the rapporteur for that project.

We are always responding to a crisis in the case of Poland and Hungary, always too late, and a conflict ensues, leading to the polarization of the entire debate. Ultimately we do not achieve the aim of upholding democracy and the fundamental rule of law. So we want to eliminate the arguments behind which autocrats like Victor Orban hide by saying: “Oh, why us? Why are they singling out Hungary? This is anti-Eastern Europe.” That is why we proposed this annual cycle where all member states are assessed against the same criteria, including democracy, rule of law and fundamental rights.

The Parliament’s proposal was that the assessment be done by a panel of independent experts; the Commission has chosen to do the assessment itself. We have such a wide range of mechanisms, like the CVN, but too often the Commission relies on the input of the members of the governments. If you take the Justice ScoreBoard, Hungary always did fantastically well, so… From what I hear, this time the Commission has spoken to a range of actors (they say over 300) so we hope that we will get a more independent, complete and accurate image.

Is hoping good enough though? Because over the past years there have been many reports coming in by the Commission which have praised Bulgaria on improving, even though on the ground the situation was getting progressively worse. And now we find ourselves at a point of unprecedented protest. When the public hears that yet another report is coming, the prevailing question will be rather when and what concrete actions can we see?

Firstly, I believe the report will be good, because countries where there are problems with corruption and authoritarianism (and often the two go together), cannot hide behind being singled out. But I also believe that it will trigger what I call “the Eurovision song contest” effect: the music is sh*t, but no one wants to be last. So they will complain, point the finger, but then secretly they will be pushed to do better, like with the European Semester. Does the Semester mean that all members fully meet the criteria? No, we know that. But at least it has a disciplining effect for them to go in the right direction.

Now, I understand the desire for action. But we do not have a cavalry to send charging in and to remove the government, it does not work this way. It is all very complex and has a lot to do with the way the European Union is constructed. The EU Commission is supposed to be independent, but in reality it remains shy in taking European member states head-on, because it is still the member states governments who nominate Commissioners. The Commission has to get used to this new role. You can also see that it is politicized and that the member states are resisting like mad, as we saw with the arguments this past summer over the budget. They left everything vague, as they always do, and now they are asking the European Parliament to fix it. And this is difficult, plus the pressure is immense.

For example, my government – the Dutch government – are keen on having this rule of law clause, but at the same time they find it awkward. Because if there is a Council summit, and then there is the official lunch, and Mr. Rutte sits next to Mr. Borissov and says: “Yo, Boyko, can you pass me the salt, please? And by the way, can you please not destroy the rule of law?” I always give this example, because it reflects the events in reality. You can compare it to the impeachment procedure in the United States: a lot of Republicans feel uncomfortable with President Trump and yet they were unable to vote according to their conscience because it is a closed club, this is how it works.

My initial proposal was to have an automatic trigger: if you have an annual report and it has multiple red flags, then there should be an automatic sanctions mechanism. This proposal did not make it. But ultimately, no matter how you organize it, it will always be a political decision to take action. We do not have strong central powers, it depends on the member states and they do not want to make Europe stronger. There are lots of Dutch people who are looking at countries like Bulgaria and saying: “Why isn’t Europe acting on this?” But then you clarify that for this to happen, they need to give Europe powers, and they immediately go on the defense. So there is your dilemma.

This is all pretty bleak, but I do think that despite Poland and Hungary being off-track, had they not been in the European Union, it would be much worse. There is a mitigating effect, being in the European Union and seeing that the institutions care. I can understand the Bulgarian people are feeling that no one takes interest in Bulgaria and I agree that the EU has been slow to act, but that is also because of the novelty of the situation. But do not think that there is no interest. We will be monitoring on a regular basis.

I want to walk you back a bit, you said that ultimately decisions for action are always political. Bulgaria fares much worse than Hungary or Poland in multiple rankings measuring democratic norms. Do you think that the silence on Sofia is due to the ruling party GERB being in the European People’s Party group?

Clearly. The EPP is a big power machine and they tend to be very protective of their political family. The same goes for other families. My political family has had its share of awkward cousins, and some of them we have checked out at some point, but it remains difficult.

Mind it that when I say political, it is not necessarily partisan. If you look at the Council of the EU, even if the members all belong to different parties, it still behaves like one body. The dividing lines can be party-political, they can be North-South, they may be East-West, small-big. There are different factions and they all have this shared interest of not strengthening the hand of the European Union, they would like it to remain firmly inter-governmental because it is in their own interest. They think in a national – and often nationalist – way. But there is the dilemma that we mentioned: you cannot have an inter-governmental weak Europe and expect Europe to intervene in member states.

In Europe things move slowly, but when they move – they move. The issue of the rule of law has been rising on the agenda rapidly. This report will also strengthen the hand of the European Commission, because now if it intervenes, they will have better justification. Will it solve all problems? No. But is it an additional tool? Yes. It is not an ultimate solution, but it helps.

Another way to help and encourage, according to some, is cutting European funding. Do you think that is an effective tool as well? Should money be tied to rule of law?

Yes. This is the conditionality of the budget, but this is not the ultimate solution. The idea came to the Council, because they had this problem called Victor Orban and they thought this was awkward because when they are sitting at the table, they want to avoid making decisions about each other. So they decided: “Oh, if we know we have budget conditionality, some anonymous official from the EU Commission can do the assessment, and tick all the boxes, and then we cut the funds”. Of course, that is an illusion because it can never be done by an anonymous Commission servant: it will always have to be a political decision. So they cannot escape their responsibility.

The impact of budget conditionality will not be the same for all member states. Take Austria, where there is an issue with rightwing tendencies and corruption. But Austria does not rely as much on EU funding, so how do you tackle that? It is not an equal instrument. Just a tool in a toolbox, but it will not solve the problem.

We are considering “smart conditionality” because we do not want autocrats like Victor Orban benefiting from EU funds, but we also do not want to penalize the people. “Smart conditionality” would mean that if there is an autocratic and corrupt regime, the Commission could take over the management of the funds, so that they would go directly to the beneficiaries, rather than through national authorities and that way we could keep a better eye on the money.

Sounds like a hard task.

Well, nothing is easy [laughs].

I did want to ask about the “awkward cousins” in European political families. Are there mechanisms for sanctioning “rogue” members of a family who do not adhere to common values? Earlier this summer the Chairman of your political family Renew Europe Dacian Ciolos was fed false information by the Bulgarian Movement for Rights and Freedoms in relation to the protests, for example. Ciolos later admitted to being misled and apologized. How can this be addressed?

In practice it is very difficult, but it happens occasionally. Orban is an example. We had the Austrian case as well. It all depends: if you are in power, it is more difficult. If you are not in government, it is quite easy. These power structures are strong.

Thanks for all the messages on my tweet about events in Bulgaria. Well received. With additional details on the situation, and having analysed the facts, they have not been well reported indeed.

— Dacian Cioloş (@CiolosDacian) July 16, 2020

As it has always been, rule of law is and will continue to be my fight.

So in this case do European MEPs have access to independent, verified information about events in member-states or do they have to rely on national politicians, who are often embroiled in national dynamics and will privilege them to European matters?

Of course. As the chair of the monitoring group, for example, I would get a lot of emails from individual citizens, we also have their NGOs, we send questionnaires to the governments, we speak to them and invite them to hearings, we speak to the Council of Europe, the Venice Commission, GRECO: there are so many organizations, endless sources. Things cannot be held secret. It is 2020. You can follow events in real time.

It is not just knowing the facts, but how to interpret them. Very often what you see from a country like Bulgaria is that you get different MEPs, from different political groups, telling you different versions of events, all of which contradict each other. And I cannot judge what is true, but I do know one thing: in such situations, when there are such widely diverging interpretations of the facts and so much confusion – that in itself is a problem. It means people cannot trust the authorities, with little difference which version is true.

We stand with all people in Bulgaria – and all countries – who are clamoring for clean, transparent, and efficient government, dedicated to the people. And if you are Bulgarian, you are an EU citizen and you are entitled to that kind of government. We should not create the illusion that the European Union as an outside force can solve every single problem, but we will always firmly stand with those who advocate good government, transparency, fight against corruption and for the rule of law and fundamental rights.

Cover photo: © Stephanie leCocq / EPA

„Тоест“ се издържа от читателски дарения

Ако харесвате нашата работа и искате да продължим, включете се с месечно дарение.

Подкрепете ни